The Jeep

The Jeep

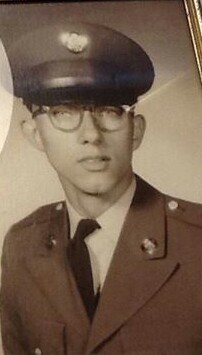

In the summer and fall of 1966, I was known as Specialist four, (E-4), John D. Riggs. In that year, I arrived in Vietnam and was assigned to the Army Security Agency, 337th Radio Research Company, attached to the 1st Infantry Division, based in Di-An, South Vietnam.

My primary job was MOS 05H20, (high-speed Morse code intercept operator), but in the military, as an enlisted man, you can and will be assigned to other work details, such as filling sandbags, building bunkers, KP or any other work as deemed necessary.

On September, 24th, 1966, I was assigned as driver for our company executive officer, Lt. Dennis Hart for a trip to Bear Cat, about 30 kilometers away, near Long Thanh. He was a first lieutenant, and as I found out later, was something of a celebrity in the 1st Infantry Division, often referred to as a “Wunderkind” because of his youth, military bearing and prior work for one of the division generals. He and I actually had a bit of a run-in weeks earlier over my failure to salute while on guard duty one day. Since we’d had that history, I was surprised that he would pick me as his driver for this trip.

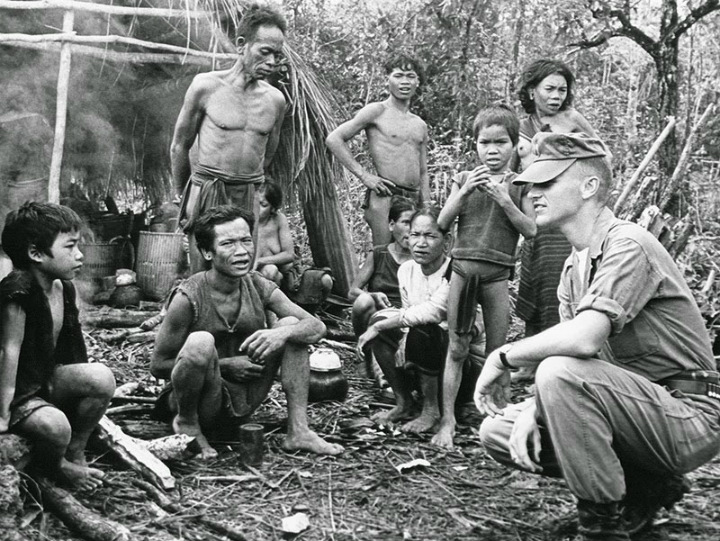

Our jeep would be following the company commander, Captain James Stallings and his driver, Specialist Thomas Herring, who was the company clerk at the 337th. As I was told, the captain was going to Bear Cat to visit some elements of the company who were on temporary duty involving radio direction-finding.

When we arrived, we dropped off the officers and left the jeeps to go to the mess hall for dinner. Afterwards, Lt. Hart told me that he and I would be returning to Di-An, and that the captain and his driver would come back the next day with a scheduled convoy. I was a little worried about the danger of driving back in the evening over sometimes unpaved roads that passed through small Vietnamese villages and settlements. Even though people would generally smile and wave at us, it was not altogether a comfortable ride.

Lt. Hart seemed particularly concerned about our safety and reminded me to drive in the center of the road, away from the fringe that could be easily mined. We didn’t make much in the way of small-talk on the trip until a somewhat heated exchange when an elderly man rode his bicycle directly in front of us as we passed through a narrow village road with a thick tree line on both sides.

The lieutenant told me to speed up and hit him, “run him down and get us out of here!” I politely declined to do that, but before there was any further discussion, I laid on the horn, veered sharply left and accelerated past the bicyclist, missing him by only a fraction of an inch. We made it back to Di-An in silence but without further incident. I dropped off the XO, who exited the jeep and walked into the headquarters building without saying a word. I turned in the jeep to the motor pool and was done for the day.

The real story begins the next morning when we all found out that the convoy in which the captain was riding had been attacked enroute by a command-detonated explosive device. Captain Stallings was killed instantly in a hail of thumb-sized shrapnel. Specialist Herring was wounded, losing his right leg. There were accounts later of ground fire from the trees after the explosion and that a Sgt Morris, on the same convoy, heroically pulled the captain out and away from the jeep, even though he was already dead.

Meanwhile, the devastated jeep was towed to the 337th motor pool. When I saw it, it was raining lightly and the rainwater mixed with the dried blood on the floorboards of the jeep that had been peppered by dozens of large and small holes torn into the metal along the passenger-side. Some people took photos of the jeep. I didn’t, but the image stayed clearly in my head for all the years afterward.

A few days later, everything in our company changed. I never saw Lt. Hart again, having heard that he was reassigned. Not long afterwards, I was in a small group when the company First Sergeant reported that he had met with Specialist Herring in a hospital in Saigon, reporting that he was doing well and even joking and flirting with the nurses. His optimism seemed strained and none of us completely believed that.

My wife and I lived in Southern California in the late nineties and we frequently visited the Santa Barbara area. It was there, at a Borders bookstore, that she bought me a coffee-table book on Vietnam War art. It was published in 1998 and titled “The National Vietnam Veterans Art Museum, Vietnam, Reflexes and Reflections.”

In looking through the book, I came upon a photo of a jeep that had been heavily damaged and pock-marked with holes as part of an art submission. I had no photos of my own but my memory was jarred by this picture with the specific pattern of holes and blood stains. Iwondered if somehow this could be Captain Stallings’ jeep from September 25th, 1966.

The photographer/artist was listed as Keith Decker, a former medic with the 1st Infantry Division based in Bien Hoa, Vietnam in 1966. I made the assumption that it was very probably the same jeep, but having no way to confirm this, I put it out of my mind for over twenty years.

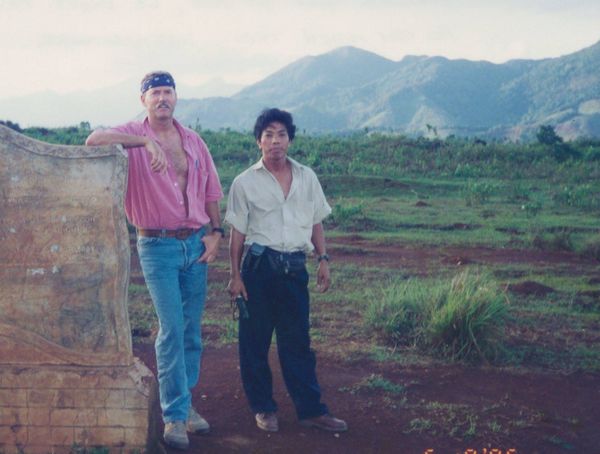

Recently, I was contacted by SFC Robert Wiltzius, historian for my former ASA unit that is now located in Fort Hood, Texas. He asked if I had any additional information on the death of Captain Stallings for an online tribute. I told him about the photo in the art book but wasn’t able to confirm that it was the same jeep until I was sent a photo from former Battalion Training Officer, Ed Wiessing, now a civilian, who had developed it from an archived negative of a picture taken at the motor pool a few days after the attack.

The identity of the jeep is now confirmed by comparing the pattern of shrapnel holes in both photographs.

In researching all this, I was able to make personal contact with Keith Decker who is now living in Chicago. We spoke on the phone and he remembered the photo. He told me that he believed the ambush took place right after leaving the gate and the picture was taken after the jeep was towed back to Bear Cat immediately after the attack.

In the spring of 2022, I was fortunate to be selected to be part of the Utah Honor Flight on June 7th and 8th, out of Salt Lake City. Honor Flight is a program for veterans of WWII, Korea and Vietnam to visit memorials and monuments in our nation’s capitol free of charge. I saw the opportunity to do something particularly meaningful to me when our tour buses reached Arlington National Cemetery to watch the changing of the guard at the Tomb of The Unknown. My goal was to place a coin on the tombstone of my commanding officer.

Captain Stallings was buried at Arlington Cemetery, and knowing from the itinerary that I would be there with the Honor Flight, I carefully mapped out the coordinates and distance to his gravesite in hopes of being able to get to his grave to leave a coin marking my visit. With my Honor Flight guardian, Julie, we raced almost half a mile into the cemetery after we hurried off our bus after stopping in the bus parking area at the Tomb of the Unknown.

We found the Stallings gravesite after a hard jog through wet grass and many thousands of grave markers, using my phone as a GPS. We left coins on the stone and took pictures. After another fast run, we made it back to the group in time to watch the changing of the guard without causing any disruption to the others in the group.

I will remember this for the rest of my life and am so very grateful that I had the opportunity to be on the Utah Honor Flight!

That’s my Vietnam story. It’s about a violent event that took place over half a century ago and the odd coincidence of finding a picture in a book that was from out of my own memory.

Like a lot of war stories, this one doesn’t really have much of a satisfying ending. It just keeps going on in my head, leaving more questions than answers.