The Sights and Sounds of Vietnam

There was a lot of repetition during the war. Daily routines included: patrols, many of the same sights and smells, trudging through rice paddies, and performing guard duty during the pitch-black darkness of night. Sleep was hard to come by with all the interruptions and you learned to take cat naps whenever possible. Here’s a soldier’s take on it all.

By Preston Ingalls

“Ingalls! Ingalls! Wake up, man.”

“Uu-h-h-h! What?” I groggily woke to someone shaking my shoulders in the dark.

“Ingalls. Your time, dude. C’mon. Guard duty. Let’s go. I’m tired.”

I slowly arose from the canvas cot, and my eyes began to burn. The previous night I had been awakened for guard duty to find my lids swollen shut from mosquito bites. Tonight, I had rubbed mosquito repellent on my face prior to falling asleep, and now it was slowly dripping into my eyes.

“Damn,” I said, dabbing my eyes with the corner of my shirt.

The grunt, Sgt. Ellis was hovering over me. “Hey, man. I’m sorry, but it’s your turn at guard duty. I’m getting sleepy; I can’t keep my eyes open, man. I did my three.”

I shook my head trying to squeeze the tears out, which only seemed to accelerate the stinging. “No, Sarge. Not you. It’s my damn eyes. I got repellent in them. It’s burning like crap. Jez!”

Ellis laughed and stepped back for a few moments to ensure I was awake before returning to his own cot. It wouldn’t have been the first time someone was awakened for guard duty then fell back to sleep, leaving our position unguarded.

I got up and stretched while I tried to clear my eyes. “It’s cool. I’m up. I’m up. Got it, Sarge. Got it.”

Dang…no rain. Groovy.

I grabbed my M16, propped at the foot of my cot, as well as the steel pot, as we referred to the helmet. We berthed under the stars outside the armored personnel carrier (APC) because it was too crowded to sleep inside. The stench of dirty socks and the prospect of being elbowed at night, along with the chorus of snores, made the interior of the APC unappealing except during the rains, when we would “pack ‘em and stack ‘em.” I had camped out a lot with my family before joining the Army and found it more tolerable to sleep under the sky than some of my comrades did.

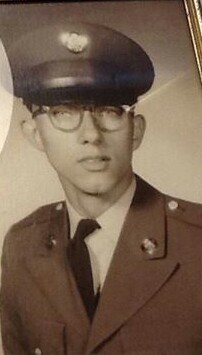

Heading for guard duty—daytime—FNG before field assignment

Reaching under my cot, I found my web belt, which held my gear, including a canteen. Removing the canteen from its canvas holder, I tilted my head back to flush my eyes with the tepid water. It brought a little relief.

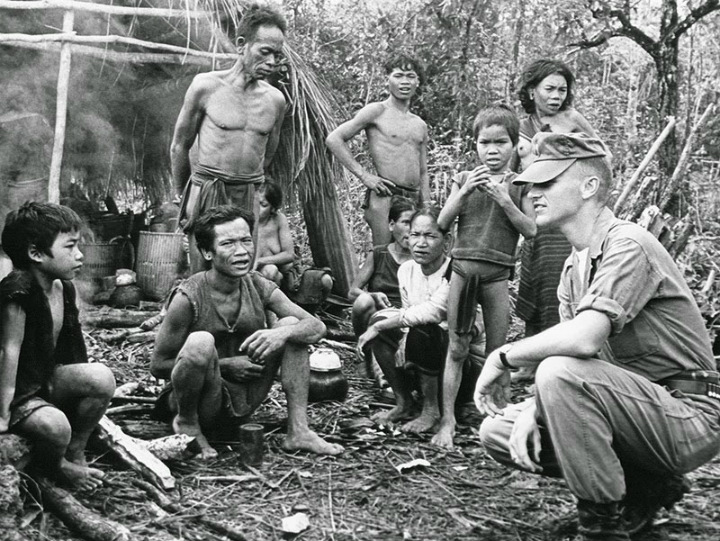

Guard duty was three hours per night for each of us unless we were on high alert. Then, we had two on post at a time. There was another track to my left about 10 meters, and the local South Vietnamese ARVN headquarters bunker was exactly to my right, about 20 meters. There was movement on the top of the track to my left, track C-21, another Charlie Company track with the motor pool guys. They must be changing over guard duty as well, I thought. I looked to my right to see if there was any movement at the Vietnamese (ARVN) bunker. There was none. Either the guard was patiently scanning the perimeter, or he was steadfastly asleep, a common occurrence with the ARVN soldiers. I hoped it was the former instead of the latter.

The foreground was a blanket of silhouettes, dark and foreboding with black jagged shapes plastered against a gunpowder gray background. The nightline of swaying palm trees could shelter the stealthy enemy, bent on harm and the termination of my existence. Suddenly, I felt so small in the scale of things, but my heart was large and it was aching. Apprehension was replaced with undying affection. It brought life where death could happen with an eye’s blink. The thought of Cynthia was like a soothing breeze on a hot day.

I blinked to readjust my vision after peering through the scope, but it only accented the stinging from the mosquito repellent.

The jungles nearby were always noisy. With the clamor of the local livestock, barking dogs and jungle sounds, I was amazed I could fall asleep so quickly after my guard duty. The sounds began to taper off somewhere around 1 a.m. and reignited at sunrise. Jungle birds and insects chirped and sang, interrupted periodically by a village dog. It was strange to sit there and gaze at the remarkable celestial bodies, take in the ensemble of sounds and smell the mix of odors from sweaty GIs and the village while scanning my front for movement by a stealthy enemy trying to penetrate our position.

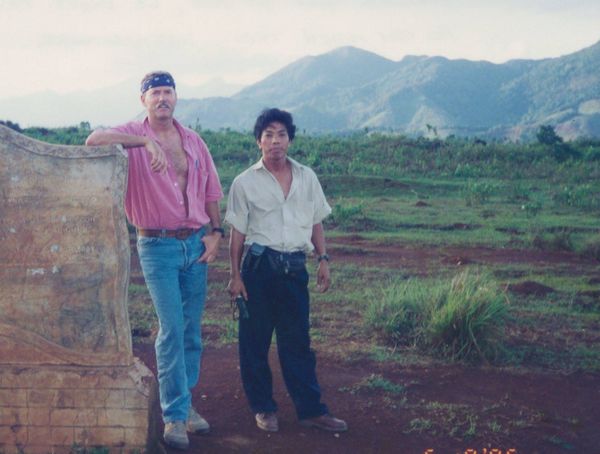

Sitting on top of the track that night, I thought of driving down the highway on top of our APCs. The striking splendor of Vietnam astounded me on these drives, and I often thought, “What in the hell is a war doing in a place like this?” I made a mental note to return to this country when no one would shoot at me.

I was assigned to a track responsible for patrolling and securing the local area of operations with the rest of our unit. We all couldn’t sleep inside the track at night, so after erecting concertina wire around the perimeter and chain link fencing in front of the track to take the brunt of a grenade, B-4, or RPG rocket blast, we always erected a tarp to congregate under in the rain. Although the tarp provided some solace, monsoon rain came in at all angles based on the wind, so a soldier stayed dry only in the dead center. Sometimes monsoon rain can come down horizontally, so even the center was no guarantee.

We took turns sleeping on the outer edges. The hammering rain was merciless at night to those inhabitants of the border. The droplets were weighty and rapid. The staccato battering distracted us from the sleep our fatigued bodies screamed for. It was common to wake up with a two- to three-inch puddle of water in your cot and soaked to the bone. Dry socks were kept in a plastic bag inside the track. Unfortunately, demand was high and supply was low. After a couple changes a day, we ran out. We bartered precious items like cigarettes and Military Payment Certificates (MPC) to acquire more socks. In no time, most of us contracted some form of foot fungus that we took back as souvenirs to the States. I still have scars between my toes.

Guard duty was a real struggle. When a soldier perched on the track for guard duty, the plastic poncho provided some form of coverage, but the face had to be exposed to conduct a 180-degree visual scan of your position. In the States, rain fell in droplets; in Vietnam, it descended in pellets with brute force.

As the rain feverishly struck my face while I struggled to view the area in front of our track, I imagined my girl, Cynthia, sitting there with me. Huddled under that poncho with wet fatigues and soaked underwear, I was dry and cheerful with my thoughts. I even found myself whispering to her. Sometimes I retrieved one of her recent letters from a pocket and drew it under my thin plastic poncho. I inhaled the faint scent slowly with my eyes closed. It was a brief respite from the misery presented on the opposite side of that poncho—a world that held me hostage.

After a few minutes, with great reluctance, the momentary reprieve ended, and I returned to my role as a guard, momentary custodian of security. Grabbing the hood and sliding it down to expose my face, my return to the bleak and wet night was complete. I was then faced with staring intently at the perimeter, struggling to detect movement, all the while being battered by the voluminous pellets of water. Because I wore glasses, it was a continuous battle to keep them from blurring and restricting my vision. I couldn’t see with them, and I couldn’t see without them. Humorously, I reassured myself that the stealthy enemy was pretty bright and had no interest in sliding through the deep rice patties of water putrid with buffalo dung and mosquito larva to sneak up on us. I hoped. Still, it would be an opportune time so caution was the calling card.

The First Sergeant would yell: “OK, ladies. Off the track and into the paddy. Let’s get these stuck tracks out. Get the cables hooked up. Let’s go! Let’s go! Hubba-hubba. Move it. Shake it, ladies. Move your asses”

When I jumped off, the mud sucked me into the earth like it was consuming me, pulling my body into its womb. I often got so mired in the mud that I would lose a boot while trying to move around. It made a loud sucking sound and then a pop as my foot left the boot. It was a funny and common sight to see guys balanced on one foot while bent over searching for a buried boot with a mud-slathered hand.

Once a dried corner of the track or the center of the tarp was accessible, I mentally blocked out the smell of dirty socks, the invasion of mosquitoes and other small jungle critters, mildew and my buddies’ digestive odors, to write or read letters.

Cynthia’s poignant letters never failed to inspire and lift my spirits. The content of my letters to her were more about how I missed her or something I had read in a magazine recently. It was less about the bleakness caused by relentless rain and the difficulty of wet clothing. The banter was harmless, and I tried to avoid depressing topics.

Dampness was ubiquitously present and clutched to everything like fresh paint. Between the extreme humidity of the tropics and the unrelenting monsoon, the wetness saturated my skin and psyche. In conversation with others or just solo utterances, rain was a four-letter word. It was almost always preceded by a series of colorful adjectives that did not pay homage to H2O.

At night, the critters of the jungle sang their mating songs through clicks, screeching and odd noises, hour after hour. Sometimes on guard duty I would focus on trying to distinguish one sound from another. To pass the time, I tried to envision the animal or insect responsible for that particular sound. It helped to kill the tedious hours of watch. Even timing the intervals between the isolated sounds on the luminescent hands of my watch became an entertaining exercise.

During the day, the sounds were a continuous roar with the bellowing screams of our APC engines, the hacking chop of helicopters overhead, and yelling voices of soldiers sitting high atop the APCs.

As if there was not enough assault on the eardrums, let there be a firefight or recon by fire. ‘Recon by Fire’ happened when we lined our tracks up facing the jungle tree line after the bad guys had been spotted by circling helicopters.

There are no other sounds or smells similar to jungle war. While many of those kids I had gone to school with were having their eardrums blasted by loud rock music back home, my eardrums were peppered by the sounds of explosions and loud weapons fire, which would later result in some permanent hearing loss.

Next night…more of the same. Next day…repeat.