“Facing the wall and a story of healing.”

My name is Kenneth Bopp, and I am a Vietnam Veteran. I could tell a war story as well as the next guy. I thought I was home-free and did not have any problems. Most of the pictures of that time are either missing or put away in some box and are never brought out; Just like the traumatic memories have been placed aside as well, I remained at ease with my life that way.

I served with the U.S. Army, 44th Medical Brigade, 24 Evacuation Hospital, and USARV. Then something happened that shook me to my foundation. It did not come from another Veteran, my family, any friends, or co-workers. It came in the mail, in a plain brown wrapper in the form of the National Geographic VOL. 167, NO. 5 May 1985. I will remember that day as long as I live, for that was when I realized who I was and where I had been. ‘The Wall’ had been in existence for almost two and a half years, and I really knew nothing of it. As I read alone, I found myself having to really struggle to see the print. I suddenly realized that I was trying to read through tears, which eventually turned into racking sobs that frightened me. I struggled with these new feelings of unrest. I felt the family was walking on eggshells as if they were afraid that anything they said or did would send me off on another crying jag. I found I could not listen to any music from the sixties, or of that era on the radio. I always found myself crying.

I tried not listening to the radio, but the music was in my head all the time. With help, I came to the conclusion that the only way to heal, was to visit ‘The Wall’, and that visit must be made alone. I arrived in D.C. on a Sunday and headed for the ‘Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial.’ Shaking off the strange feeling that enveloped me, I walked up the slight rise and looked around for the listing book to look up the names I wanted to visit. All of a sudden, I found myself shaking. I turned around and walked back to the bike. After smoking a couple of cigarettes, I again walked toward the listing book. Again I started shaking and decided to approach the memorial from the other side. I stood looking at the statue of the three troopers and still felt fairly calm. The stark beauty of ‘The Wall’ struck me. It was magnificent. I could actually see the reflection of the visitors, even though the tears in my eyes. I approached the listing book and looked up the names of those I wanted to visit, and finally began my walk along ‘Th e Wall.’ Th e first name I went to was that of a family member of a friend. Stepping back, I spoke to him, explaining how I happened to be there and my gaze took in the many names carved around his. I began to cry, silently with a blinding realization that I might have taken care of some of these men during my tour in Vietnam. I did not remember even one of the names, or faces of those placed in my charge as a nurse anesthetist! I finally remembered one trooper that I was caring for in the emergency ward at 3rd Surg. He had multiple fragmented wounds of the abdomen and a wound on one eye. The eye wound was deemed not serious enough to transfer him to another unit for eye surgery yet, because he needed his belly taken care of first. He kept saying, “What a terrible way to die”.

I told him his wounds were not that severe, and that he was not going to die. He eventually calmed down and stopped talking about dying. As the bearers came to take him, he looked at me, grabbed my hand, and blood began pouring from the eye wound, his mouth, nose and ears. He died. I had unknowingly, lied to him by telling him he was going to be all right. Feeling desolate, the tears flowed freely as I apologized to them all. I returned to “Th e Wall’ the next morning, and after a few minutes of meditation approached one of the volunteers who recognized me from the day before. They saw the behavior of a first timer and always kept an eye on them. Maybe I was not alone in this thing after all. Directing me to a spot that would serve my purpose, someone said, “Welcome home, brother”. Except for my family on my return, not one person had welcomed me home. Perhaps I was “coming home” finally.

I placed my letter in the fissure between two of the panels and stepped back. Of course, there were more tears, but they were more of a balm than the acid I had been enduring since reading the National Geographic issue. I then saw a great bear of a man in a wheelchair. He had no legs. He had on a baseball cap and vest, both covered with pins, medals, and patches. Our eyes met, and I offered my hand, saying, “Welcome home, brother”. We exchanged unit designations and locations ‘in country’. He asked me how I felt after my visit to “The Wall”. I told him of my feelings of guilt and sorrow for not remembering names and faces of those I cared for. He said, “You did something over there, and I am sure you did it to the best of your ability. Had you not been there, who knows how many of us would not have come home at all. All of you that were there to help the wounded did a difficult job. You feel guilty because you came home, and they did not, because you did not do as tough a job as others, but that is just not true.

None of us that were there liked anything about what we were doing, but we did it. And I feel we are the better for it”. I thanked him and asked how he became so perceptive. He said he spent a lot of time around ‘The Wall,’ had talked to a great many people and heard many stories, and said the way I felt was one of the more prominent feelings among the medical personnel located in hospitals. It was evident in the way they spoke and looked. Thanking him again, I left as I had a long trip home to New Orleans.

On my bike return home, I was so high after my visit, I found myself screaming to the sky, “I’m alive. I’m alive. Thank God, I’m alive.” We soldiers went to Nam together and some of us came home together, but none of us came back whole. Thanks to those that conceived ‘The Wall’, in the face of daunting odds, we veterans now have a healing place to visit.

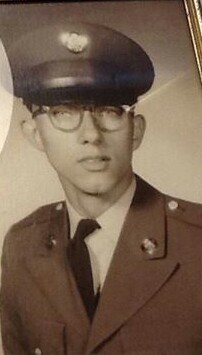

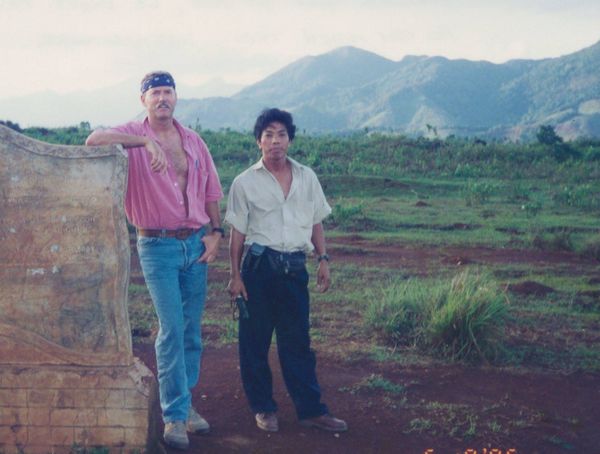

This picture is of an awards ceremony where I believe we all received the ACM, Army Commendation Medal. I also received a Purple Heart medal for wounds received on a previous deployment. Pictured left to right: Col. Robert Leaver, unknown, myself, Peggy Perri and Linda Troeger. I have recently been diagnosed with End Stage Renal disease as a result of diabetic nephropathy. I have been told that I will have to go on dialysis within 6 months. Diabetic nephropathy is atypical, in that there is no accompanying retinopathy or neuropathy. I was stationed in Long Binh, which was one of the most heavily sprayed areas with Agent Orange.

~ Kenneth Bopp, U.S. Army, Vietnam Veteran

–

Kenneth’s full story appears in the book VietnamandBeyond.com

Veteran stories are interviewed and collected by JennyLasala.com