I left my heart

Departure for Vietnam

I Left My Heart

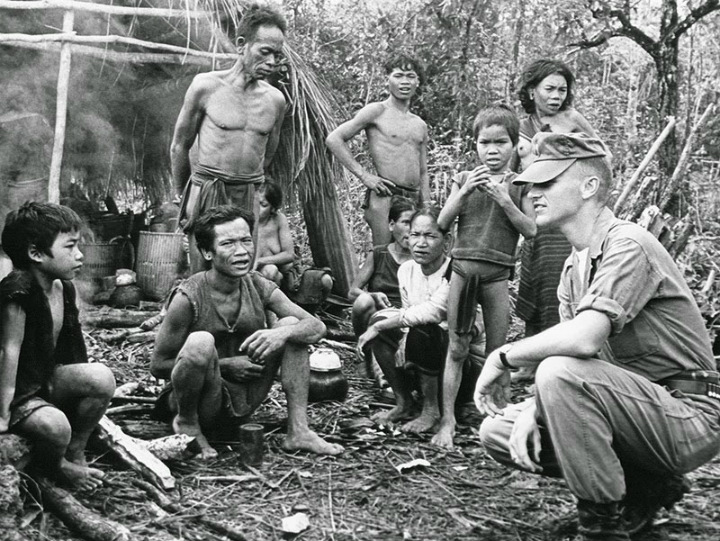

Before arriving in Vietnam for duty with MACV SOG, I was well aware of their mission. Washington level briefings by my parent agency covered the entire spectrum and sensitivity of the “Studies and Observations Group” (SOG) operations. Apparently when the covert combat element was first formed, it was more accurately called the “Special Operations Group.” Wise old men in a Pentagon back room, or possibly the legendary “little old lady in tennis shoes”, decided that the title might be too revealing and came up with a less descriptive name that retained the SOG initials. So, when I said goodbye to my family in California, where I parked them for the duration of my assignment, I knew I was not going to be “studying and observing” for the next year–more likely hiding under my desk.

Saying goodbye to family comes with the job in the military. I had done it a number of times before; but flying off to war alters one’s perspective. I couldn’t help but think of my own father who sailed off to war in 1941 and didn’t return until 1945, leaving my mother to raise two children almost the same age as my two. It’s difficult to describe the emotional turmoil: wondering how your family will cope in your absence; how they will change while you’re gone; and, should worse come to worse, how their lives will turn out without you. Respect for my father went up several notches, as did my regret that I didn’t give more credit to my mother for those difficult years of extraordinary responsibility and anxiety. As my wife and I drove from San Diego to Los Angeles, where I was to catch a flight to Travis Air Force Base and on to Vietnam, I admit that the tears flowed freely when I allowed thoughts of my children to rise to the surface.

Travis Air Force Base, outside of San Francisco, was the primary departure point for those bound for Vietnam. On a clear California morning, our C-141 lifted off over San Francisco Bay and we watched the Golden Gate Bridge fade behind us. It was understandable why, in the years to come, so many of those who served in Vietnam from all parts of the U.S. would get misty eyed when they heard the song, “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” As the 141 leveled off and the U.S. dropped away behind us, we all kept our own thoughts about what lay beyond the brief refueling stop at Kadena Air Force Base in Okinawa and the approach to Tan Son Nhut Airport in Saigon.

It was early evening as we made visual contact with South Vietnam and the anxiety level on the plane was palpable. From what we could see of the ground in the fading light, it looked pretty peaceful — lots of green rice paddies, and even some normal looking river and highway traffic. The first sign that things weren’t “normal” was the appearance of flares drifting over the city and its approaches. Every evening at dusk, and lasting through the night, the U.S. Air Force patrolled the skies above Saigon, dropping intensely bright flares which seemed to hang motionless above the city on their miniature parachutes, turning night into day and denying the enemy the opportunity to form up for a surprise attack on the city or allied military installations.

The second sign that we were in a war zone was the steep landing approach. The C-141 is a large aircraft and would normally descend gradually from a long distance out from the airport. However, flying long distances at low level is not recommended when the surrounding countryside is full of bad guys with guns.

Safely on the tarmac at Tan Son Nhut, we were herded into the terminal to receive a quick tutorial on staying alive for the first few days until reaching our final destinations. Troops were put in touch with representatives of their units for onward ground transportation to local base camps or to flights which would move them to other parts of the country. I was met by the officer I was to replace, loaded into a black jeep, and taken on a hair-raising, high-speed, no-headlights ride through the darkened streets of Saigon to my temporary quarters. I was told that the need for speed was to beat the curfew, at which time barbed wire barricades, manned by itchy-fingered ARVN (Army of Viet Nam) sentries, were swung into place across most of the streets.

August is the dry season in Vietnam — an oppressively humid period followed almost to a predictable day by the monsoon season, when the skies produce a deluge that doesn’t let up until the beginning of the next dry season. Dry season humidity is the kind that causes profuse sweating without exertion. With exertion, you are sopping wet in no time.

My first night in Vietnam, I was given a room on the top (9th floor) of a hotel in the Cho Lon suburb of Saigon. Although there was an elevator, there was no electrical power — a frequent occurrence, I was told. After humping my bags up nine flights of stairs, I looked forward to a cold shower and some sleep. Of course water got to the holding tank on the ninth floor only when the electric pump worked.

No lights, no water, grungy and sopping wet from my 9 story hike, and surrounded by bad guys. Well, at least it wasn’t as bad as boot camp.