It wasn't so bad in Nha Trang

When I got off the plane in Albany GA late September 1967, wearing my Air Force uniform for the last time, my mother hugged me so hard I could barely breathe. She wouldn’t turn loose. Only now can I see that having come through WWII, she had known many who did not return from war.

I, on the other hand, had, and have, fond memories of Vietnam. It was a lark. Only got shot at once, that I know of, and that bullet went through our plane and out the roof a few feet from where I sat staring at a screen full of electronic blips of Morse Code, radio signals from the Viet Cong. I flew 125 missions on aging EC-47s, the two-engine workhorse you see in all the old movies.

The missions lasted up to seven hours, sometimes during the day, sometimes at night. The greatest danger was probably catching a cold since we started off sweaty and hot and rose to the cold of 10,000 feet. We used direction-finding equipment to locate Viet Cong transmitters, usually flying at an altitude that was out of danger. Once my crew and I had to put on parachutes and get ready to bail out because of a faltering engine, but we landed safely.

In fact, the most danger I ever felt was finding my way back to our barracks while drunk. We always had plenty of beer and liquor, way too much in fact. Nha Trang, where I was stationed, was said to be a rest and recreation destination for both Viet Cong and U.S. personnel. Beautiful beaches, hotels, restaurants and shops. I got a pair of custom made black and cordovan saddle oxford shoes for about $30.

Women, too. I still have a vivid memory of the tall blonde Australian woman dancing on the top floor of the large hotel in Nha Trang. I marvel at the memory of a woman completely naked in front of 200 drinking, shouting, stomping, sweating soldiers. I always wondered how much she got paid.

With all the bar crawling, Vietnam was sort of an extension of my college days with enough danger to make it exciting.

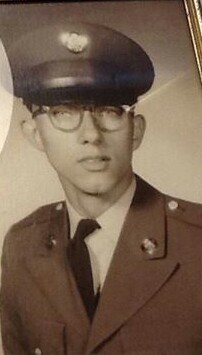

My service started that summer in 1964 when I called my draft board in Albany GA to see if I had enough time to get enrolled in college and get a deferment. I was driving a truck for Sears trying to earn enough money to get back in school and thought maybe I had another six months before my number came up. But they told me if I didn’t get in school by September I’d likely be drafted, so I decided what the hell, I might as well enlist and at least stay out of the trenches.

The Air Force recruiter told the best lies about how service would improve my life, so I signed up to wear blue. It was a good choice. Basic training was fun, running, marching, shooting, taking aptitude tests. In movies you always see that PhDs get assigned as cooks, but my experience was different. The smartest guys got to go to language school and the next smartest got to learn Morse code. I don’t know why. We were trained to intercept the “enemy” and even though this was in 1964 the North Vietnamese and Chinese were still using Morse code. It was just one example of how primitive their military was compared to ours. The Chinese Air Force pilots, at that time, would not navigate out of sight of land for the most part.

I became part of what was called the United States Air Force Security Service. Our job, before I went to Vietnam, was to intercept radio communications from the other side, like pilots talking and radar stations reporting on and tracking our planes as they flew just outside international borders. At the time it was all hush-hush. You would read once in a while about the Russians shooting down one of our unarmed reconnaissance planes. Most of us were not flying but stationed in one of the many listening posts that circled the communist nations from Alaska to Taiwan to Pakistan, Italy and England.

I landed a first assignment in Okinawa, listening to the Chinese and stayed there 15 months. It was supposed to be two years, but the call went out for volunteers to learn some new technology that would require flying over Vietnam to locate radio transmitters. It sounded exciting, going to war, getting to fly, getting extra flight pay ($50 a month). I also calculated that because of a quirk in Air Force regulations, I might just be able to get out of my enlistment sooner than my four-year commitment.

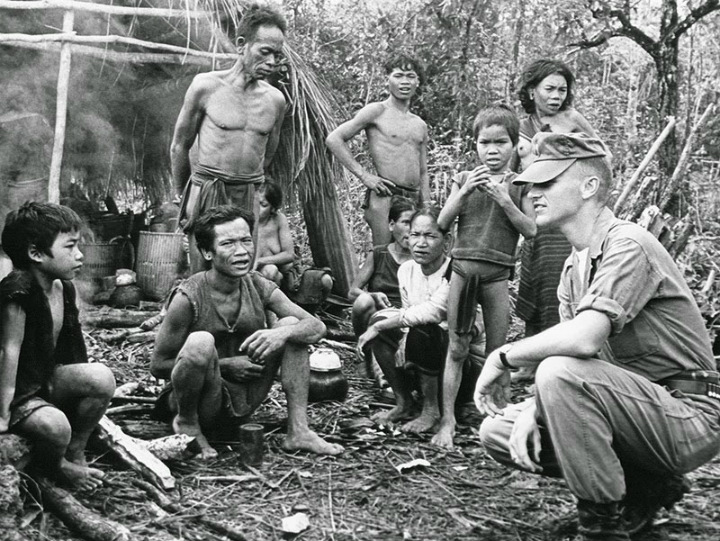

It was more fun than I expected. I got some training with parachutes, although we never actually jumped from a plane. Survival school gave us experience in how to stay awake for 24-hours while being sprayed with cold water like a POW, how to run through a forest being chased by “enemy,” how to make a bed in the jungle… it was way better than the Boy Scouts.

Then in September of 1966 I landed in Nha Trang. At first we had no planes so we enlisted scum were assigned to whatever hard labor needed doing. For a while we built foundations for buildings out of huge mahogany timbers from the Philipines. These logs would sit in the sand without rotting, we were told. All I knew for sure was that we had extra heavy hammers and hardened nails because the wood was so hard. My arm gets sore just thinking about it. Another duty was sorting through pallets of beer that were stranded in a vast field, stored because more beer was coming in than could be helicoptered out to the troops in the field. Our job was to squeeze the cans to see if they were rusted through – this was pre aluminum – and if the can was punctured throw it in a trash pile.

We figured out pretty quickly no one was counting and brought a pickup trump into which we loaded unrusted cans of beer for our own use. We found a place that would dump crushed ice to cover the load so it was crispy cold by the time we got off work.

We lived in barracks near the airport made mostly of louvered asbestos to allow ventilation. We each had a metal locker, 30 inches of space and 2-man bunk beds covered with mosquito nets. Next door was a shower that had hot water most of the time. A couple of mama-sans swept up and picked up the beer cans, of which there were plenty. One night the Viet Cong got through the perimeter and blew up some helicopters not far from our barracks, but we were all passed out and didn’t know until the next day.

We did lose one plane that was carrying guys I had worked with. My mission took off knowing a plane was missing. When we got back a guy drove a truck to pick us up from the tarmac and his face was drained of blood, white as a sheet. “They found them,” he said, “all dead.”

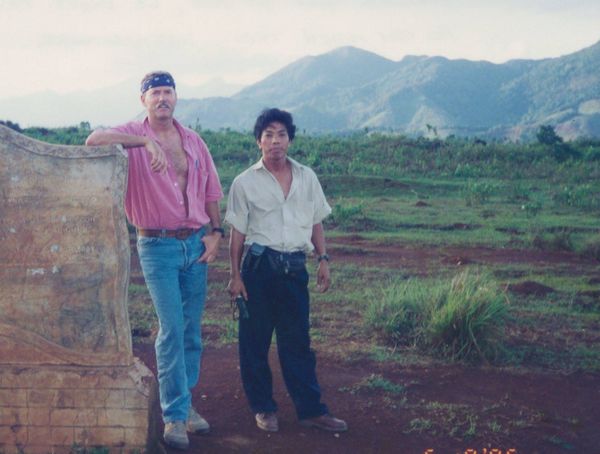

But for the most part, I was isolated from the horror. My gamble paid off and I got out of the Air Force 10 months earlier than my enlistment. I went to college, helped by the G I Bill, married, graduated, worked for newspapers and seldom think about Vietnam. When I do, it wasn’t bad at all, at least for me.

You can read more details about the Security Service and see pictures on a site maintained by veterans.

This was a great read. Thank you for sharing!

The site about my unit is https://6994th.com Lots of pictures and history.