My Mothers Machine Gun

The coincidence of reading an earlier letter from her son in Vietnam and then seeing a news report about battles in his area compelled an angry mother to take action. She doesn’t know all the facts, but knows that her boy is short of equipment and she’s going to get him what he needs. Read what she did in my article this week.

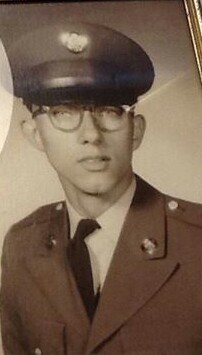

In October of 1967 my unit, the fabled 506th Airborne Infantry Regiment of World War II, Band of Brothers fame, deployed to Vietnam as part of the 101st Airborne Division. Although we did not know it then, we would be there for the bloodiest year of that conflict.

After a short orientation at Phan Rang, we were sent to the field, Search and Destroy the Army called it; but to us, we were chasing Charlie as the saying went even though we rarely caught up with him at first. Since we were resupplied either every three, four or even five days in the field, and since I did not want my Mother to become accustomed to getting a letter from me on a regular basis, I purposefully wrote to her spasmodically, rather than regularly.

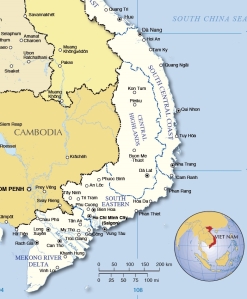

A few months later, I was sitting on an LZ in the field near Phan Thiet on the coast and more or less the center of Vietnam waiting for resupply when I realized that I owed my Mother a letter. It had been two re-supplies already, over six days, since I had last written. However, I could not think of anything to say to her.

So, I started the letter, “Here I am in Vietnam short one machine-gun for my platoon and these Bozos are sitting safely at home and are out on strike while we are fighting a war. . .” That got me started and I went on with the letter talking about how quiet it was where we were, how hot the temperature was, how beautiful the South China Sea was, how safe Phan Thiet was, then some more about the missing machine-gun and so forth. Then, I sealed it; ran it to the helicopter, and thought no more about it.

When my mother arrived home from her job at Georgetown University on February 3, 1968, she was already worried and wanted to watch the evening news. The battles of Tet ‘68 had started and they led the news. Therefore, she was particularly happy to see a letter from me in the day’s mail. She got herself a glass of wine, turned on the television to the CBS evening news, and sat down to read my letter.

“Today in Phan Thiet, Vietnam, there was savage fighting as the Viet Cong tried to seize the normally sleepy provincial capital. Units of the 101st Airborne Division met the enemy head on in a series of exceptionally violent battles that started early in the morning and continued all day. There were heavy casualties on both sides. . .”

My Mother sat there stunned. She read the top of my letter again; she read the name of the town on the screen; she read the top of my letter again; she read the name of the town on the screen. She started crying. Then, mercifully the news program broke for a commercial. The news from Vietnam actually got worse from there. She continued to cry and sip her wine.

For those of you that do not remember, CBS’s Walter Cronkite was a god, an oracle of truth at the time, and unfortunately, he was not at all upbeat about the chances of even the legendary 101st Airborne Division to hold on to the town of Phan Thiet under such a ferocious assault by a well-armed, well supplied and numerically superior enemy.

It was about the only time Phan Thiet made the national news, but we made it big time that night. According to Cronkite, the fighting was severe everywhere, up and down the coast of Vietnam, so there was no possibility of reinforcements for the embattled 101st Airborne Division in Phan Thiet. This dire prediction was his close offline for the extended news program.

Except getting up for more wine during commercial breaks, my Mother watched it all. Then, she sat there in her living room staring at the now blank TV screen. She cried for a while, then she finished reading my letter and the rest of her bottle of wine, her dinner forgotten. Her son was in trouble, and he needed a machine gun. She was sure of that.

They talked for a while. They both cried for a while. They talked about machine-guns repeatedly but not very knowledgeably, but they knew all about war. Both had lived through World War II and the Korean War by then. Finally, around two in the morning, her mother, my grandmother said:

“Let’s call Dickie.”

It turned out that “Dickie” was Senator Richard B. Russell, Jr., the senior senator from the State of Georgia and probably the most powerful Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee ever. However, many years before he had been a young boy in my grandmother’s, then Miss Varina Bacon’s class for two years at the Seventh District Agricultural and Mechanical School in Powder Springs, Cobb County, Georgia. In addition, Senator Russell’s mother, Ina Dillard Russell, was a teacher and was my grandmother’s best friend.

That was probably why my grandmother had Senator Russell’s home phone number, which she talked an AT&T operator into making a conference call to at about 3:00 AM. The two women just cried on the phone together as they waited for the call to be put through.

With Senator Russell on the line now, the three of them discussed machine-guns, and why Lieutenant Harrison’s platoon, did not have enough of them. My grandmother wanted to know exactly what Senator “Dickie” Russell was going to do about this problem of national importance, how had he let it happen in the first place and could he also see to it that the strikers were put in jail, or better yet, shot.

After midnight, both my grandmother and particularly my Mother could be of a seriously violent inclination. My Mother was the one that suggested shooting the strikers.

My father had always said that United States District Court Judges, United States Senators, and any truly pissed off American mother could cause more trouble than anything else in the world. Here we had two angry, very scared American mothers and a powerful but sleep-deprived United States Senator. Things were sure to be interesting in the morning.

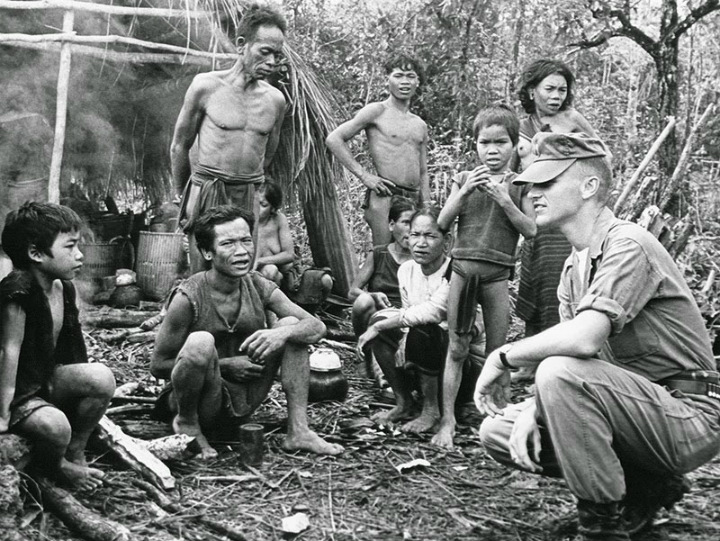

Although the majority of our training was for combat patrols in the jungle, the majority of the fighting we actually did during Tet ’68 was street fighting in the cities and towns of Vietnam. This is what it looks like. We were using trucks this time because the VC had shot up so many of our helicopters we were saving the ones we had left for Dust Off. Photo by Jerry Berry.

Meanwhile, the battles in Vietnam continued. Luckily, my missing machine-gun had been repaired and returned before the start of Tet because we had been busy. Finding Charlie was no longer the problem.

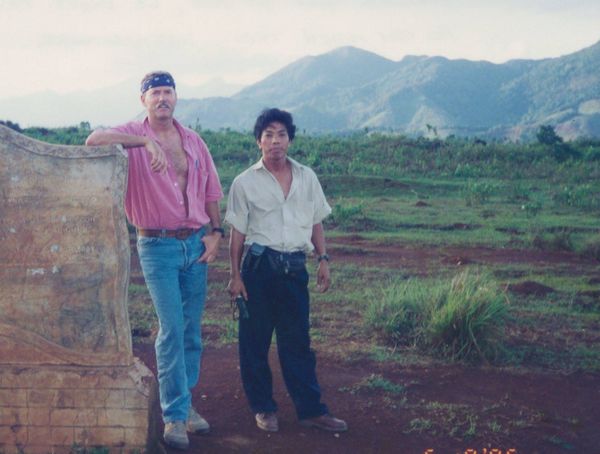

We were actually being shot at when this picture was taken. One of my men sent it to me several years ago. I am left middle in front of my RTO, Hal Dobie of Yakima, Washington. That is “Bull” Gergen, a full-blooded Cherokee Indian member of the Ranger Hall of Fame and our First Sergeant, coming up on the right. It was his second war, third tour. James Philyaw third from right. I am standing looking over a hedgerow. We are on our way back into Phan Thiet.

A day or so after the telephone call to Senator Russell my platoon was embroiled in some of the fiercest house to house fighting of the war in downtown Phan Thiet when my RTO (Radio Telephone Operator) Hal Dobie of Yakima, Washington, handed me the radio handset saying there was a man that said he was a Colonel on the radio asking for “Lieutenant John Harrison” in the clear. This violated so many Army rules and regulations that he had not answered the transmission.

I truly did not know what to do. After the third time I heard him identify himself as Colonel something or other, I have forgotten his name, and again asked for Lieutenant John Harrison I just said “Yes.” rather than saying, “This is Alpha 2-6”, meaning, Alpha Company 2nd platoon leader, as I usually would have identified myself.

The Colonel then said he had a machine-gun for me and where could he put his helicopter down so he could deliver it to me. I said I was pretty busy at the moment—after all a lot of people were shooting at us.

He reminded me that he was a Colonel, that I was 2nd Lieutenant and he demanded in the most forceful manner a landing zone, immediately.

Since he was so insistent, I said that the area in front of my platoon was wide open, plenty of room to land a helicopter, but then I had to warn him that he would be under heavy fire, both machine-guns and rockets as he landed. His choice. I think the pilot talked some sense into the demanding Colonel and he decided to leave the machine-gun back at our base camp, LZ Betty.

When we finally got back to LZ Betty a couple of days later, the Company armorer was still cleaning that machine-gun. The Colonel had tried to deliver an M-60 machine gun, to an active firefight, encased in a wooden box, enveloped in thick plastic shrink wrap, and full of thick cosmoline, but with no ammunition.

It took our armorer, Carl Rattee, three days and a tub of gasoline to get the machinegun ready to fire. But when he was done, it was beautiful.

My nickname for the gun was “instant fire superiority”, and all but one time that was true.

Strangely, unlike every other weapon in the battalion, this particular machine-gun was assigned directly to me, to Lieutenant John Harrison. It was my very own machine gun from my Mom. I liked it and when the Army made me give it back when I left Vietnam, I thought about calling her, but then, I thought it might make her angry. . .