Sarah L. Blum, Vietnam Veteran, Army Nurse

My name is Sarah L. Blum, and I am a Vietnam veteran.

I was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on December 5, 1939. Father was a jeweler, and Mother a telephone operator. My brother worked for the FAA and later with my father in the jewelry store.

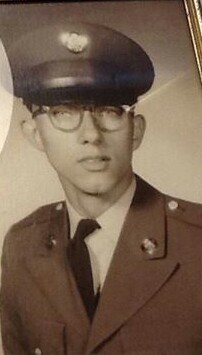

Prior to entering the service, I was a nurse working in the intensive care unit at a hospital in Los Angeles, California (1963– 1966). My father served in the signal corps during World War II, and my brother was a crew chief on Army helicopters in Germany during the Cold War. I entered the service in March 1966 and was commissioned as a first lieutenant.

The early days of training were spent at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for 8 weeks and then a 5-month Operating Room Nursing course at Letterman General Hospital in the Presidio of San Francisco. I adapted well as an Army nurse and served as:

1. Operating Room Nurse, 12th Evacuation Hospital in Cu Chi, Vietnam (January 1967–January 1968).

2. Head Nurse, Orthopedic Ward at Madigan General Hospital (January 1968–September 1968).

3. Evening and Night Nursing Supervisor, Madigan General Hospital (November 1970–February 1971).

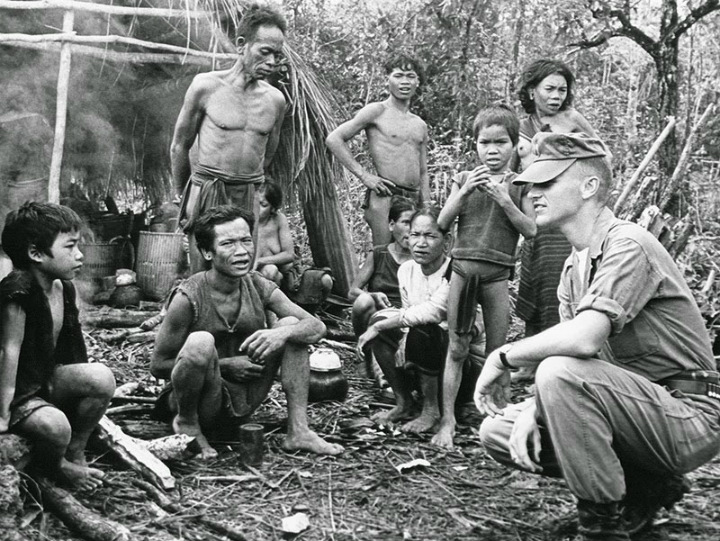

The 12th Evacuation Hospital was on the edge of the iron triangle where all the fighting was going on in 1967. We were the largest user of fresh blood in all of Vietnam. We supported the 5th Infantry Battalion, the First Infantry, and both the 82nd and 101st Airborne. There were constant mortar attacks while we worked in surgery.

My father sent me stainless steel forceps from his jewelry shop that we sterilized and used to remove shrapnel from soldiers’ eyes at the 12th Evacuation Hospital in Cu Chi, Vietnam, where I served.

There was no time for emotions. I could not show my emotions or the soldiers who came in wounded thought it meant they were going to die. Initially, I had gut-wrenching emotional reactions of horror and an incredible sadness at the utter destruction of these beautiful young soldiers. I saw the worst of humanity and what war does to hearts, minds, and bodies. There were so many young men with irreparably mutilated and mangled bodies. The constant flow of mass casualties left no time or energy to allow my feelings to flow. I had to shut them down.

I made close friends with other nurses and we leaned on each other for support. I also had a great relationship with the Australian soldiers who ran the phone system. In the middle of the night, when everyone was asleep or on duty, I would crank the phone and ask, “Are you working?” An Aussie voice would answer: “Working.” We would talk. He would listen as I spewed out what emotions I had from day and night. Then I would ask him to tell me about Australia, which allowed me to relax and get some sleep.

My mother wrote letters weekly, and I wrote back. I also had a few Military Area Radio Station (MARS) calls back home. The radio called ham operators, and they relayed the calls to close to home until I connected with home.

For recreation, we mostly went dancing and drinking—that was how I dealt with the emotions I had inside. I danced like a crazy woman.

I came home on a Southwest Airlines plane, my Freedom Bird. When I arrived at Travis AFB in San Francisco, they would not let us off the plane for two hours and told us not to wear our uniforms. It was not what I expected. It was very disappointing, but I was numb.

My friends were kind and supportive upon my return home from Vietnam, and so was my family, but outside that, it was hostile toward Vietnam veterans. I did best when I was still in the Army Nurse Corps working as an Army nurse at an Army hospital. I had a hard time outside that. I was used to dealing with life and death all the time and having intensity. I could not handle women talking about mundane things in life and could not relate to people anymore unless they had been to Vietnam.

I was at the University of Washington in my graduate course when Saigon fell. It was devastating. All the inner protections I put up to keep my emotions in started to crack. No one there understood, even though I was studying psychotherapy. They told me to “get my shit together or get out.” I made the wall inside me stronger to keep everything contained. I was totally changed by my wartime experience and no longer judgmental about other women’s choices. I became stronger within myself and had the ability to handle anything coming my way. I trusted myself. Over time I came to understand the effects of war and wounding, the inner conflicts regarding war, and the effects on our earth and the people in Vietnam. I became a specialist in healing PTSD and other wounds of war and developed a deep compassion for others and our world.

Ultimately, with 5 years of therapy, I became strong, clear, authentic, and in touch with myself, my emotions, and the Divine.

Everything changed after Vietnam. I have never been the same. It was forever changed, and I often tell people it is the gift that goes on giving. It took away my faith, which took years of work to restore, yet my faith and connection to the Divine are stronger and clearer than ever before. Because I had to shut down my feelings in Vietnam, I also had to restore my ability to feel, which took years to do. At that time my turmoil was hurtful to my relationships. I married while my depth of feeling was shut down, and when I reconnected to my inner feelings, I knew my marriage was not working and had to leave. My service in Vietnam also affected my body in a number of ways that had to be healed over time as well. My service in Vietnam was the most intense ongoing experience of my life and taught me about wounding and healing like nothing ever has. It led me to become a wounded healer with abilities far beyond anything I learned in school.

The good memories of my experience are mostly the esprit de corps we had together at our hospital, saving many lives, and loving my brother and sister service members. The worst part of the war was the day Johnny came in with the entire bottom of his body desecrated by American artillery. We had to take off his legs all the way up to his hips, and I was standing in his blood for hours, not knowing if we were doing the right thing by saving his life.

War is never okay. War destroys life in all forms. When wounds are not healing, there is a reason. Find that, and healing can take place. Separate the war from the warrior and welcome home our warriors who go in our name, even if you do not agree with why they were sent. Although I became a protester after the war, I do not regret going.

The only thing I would say is this: Never attack returning service members, even if you are against the war. I feel proud of my service now, but for many years I did not. I did veterans work for years and was a member of the board of directors of the Vietnam Veterans of America. I am now connected to many women who served and who were sexually assaulted in the military.

Sarah L. Blum

U.S. Army Nurses Corps

Washington

.

–

Sarah’s full story appears in the book VietnamandBeyond.com

Veteran stories are interviewed and collected by JennyLasala.com