To Kill A Man A Short Story by James H. Webb, Jr.

Did you ever kill anybody in the war, grandpa? How did it make you feel? How many Vietnam vets have heard these questions asked during the last fifty years? James Webb’s short story takes place during an afternoon fishing trip with his grandson when he is asked these questions. Before answering, he returns to the events of that day many years ago and searches for the correct answers. A little long, but well worth the read.

All the illustrations within are by Michael Byers

Warning: this is a long, short story!

Long before James Webb became secretary of the Navy or a U.S. senator—or even potentially a 2016 Democratic presidential candidate—he was a 23-year-old Marine fighting in Vietnam’s An Hoa basin, west of the city of Da Nang, as part of the Fifth Marine Regiment. During his tour as a rifle platoon and company commander, Webb was awarded the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, two Bronze Star Medals and two Purple Hearts for his actions in combat. An enemy grenade left him with shrapnel lodged in his head, arm, leg and back. Recounting his gritty combat tour during some of the war’s darkest days—in one eight-week period, his rifle platoon suffered 51 Purple Hearts among those killed or wounded—he told an interviewer in 1988, “My greatest feeling in Vietnam was that I was a pawn.”

Webb’s time at the war helped to inspire his career as a writer; his 1978 debut novel, Fields of Fire, is considered one of the best books ever written about the Vietnam War, and his writing ever since has often focused on combat. It’s an experience, Webb says, that the average civilian can never understand. As he wrote in his 2014 memoir, “I and my fellow combat veterans stand on one side of a great impassable divide, with the rest of the world on the other.”

This is Webb’s first piece of fiction published since September 2001.

“Did you ever kill anybody, Grandpa?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Do you feel bad about it?”

“We can talk about that later.”

His grandson looked skeptically at him as they walked, surprised and unconvinced. He did not usually deal in avoidance, but killing someone was not a subject to be discussed during a short walk in a parking lot as they headed toward the front doors of the Stuart First Baptist Church.

“I guess it must have been a hard thing to do. But I didn’t ask if it was right or wrong.”

“Well, it wasn’t really right or wrong.”

“Do you feel bad? That’s all I asked.”

It was an otherwise glorious morning. The sun hovered above them in a brilliant cloudless sky. They walked together, just the two of them, waving to fellow parishioners dressed in their Sunday best. It was their special weekend, the first Sunday after school closed for the summer, and young Abner always spent it with him. Later, they would go fishing. There was no better place to pass on family traditions than in a jon boat on the quiet of a lake, teaching a boy how to hold a spinning rod, and how to cast along the reed beds, and how to catch a bass. So just before church was an awkward time for his grandson to be asking such a question.

“We’ll talk about it on the lake.” He attempted a joke. “I grew up with Ernest Hemingway. And Hemingway said you aren’t supposed to feel bad about it.”

“Who is Ernest Hemingway?”

“Some writer who never killed anybody. Except himself.”

He had killed people, not from the cockpit of an airplane with a bomb dropped by waggling a control stick, or from a shell fired out of an artillery piece behind the barbed wire of a remote combat base, but by pointing a weapon and pulling a trigger. Killing in the infantry was different. It was not always up close and personal, but when it became personal it was also messy.

Which was why he didn’t really think about it that much all these years later. There was no denying that killing people had made him permanently different, not better or worse, just different, from the person he had been before he left and from the people he returned to when he came back home. The reality of it made the breast-beating, theoretical quandaries that dominated classroom discussions back home seem naive and child-like, imbued with the moral certainty that so often attends practical ignorance.

If you take a human life, when you die, will God punish you? Or does He give soldiers a Military Exclusion Clause? Or is there even such a thing as God?And in any event, who are we to ratify such conduct?

His answer had always been simple. Well, you either died or they did.

His postwar life would see its share of accomplishments coupled with all the inevitable frustrations, failures and disappointments of adulthood—but for him, the greatest moral mysteries had been resolved at the age of 23. It was indeed Hemingway who had written that no man truly respected another unless he felt deep inside that if it came to it, the other man would kill him. He knew the answer. He never discussed it with anyone else and he rarely thought much about it. But in knowing the answer, he also knew himself.

So when it came to war, he usually spent his time remembering the more mundane realities. The aches and pains of life in what the Marines called the Bush were with him every day, constant reminders of the war. Those, and lately the ever-too-frequent funerals of good men he had come to know as brothers—the tough, tattooed teeny-boppers who had endured it all only to return to hard lives at home and then aged too quickly and who now were frequently dying before they had a chance to gracefully grow old. Many of them had simply burned out early, their lives sapped up not so much by shrapnel and gunshot wounds, although most of them had been wounded at one point or another, but by the long-term wages of bad water, festering infections, ringworm and hookworm, trench foot and jungle sores, shrimp fever and malaria, the kinds of maladies that were so common you never complained about them to each other and yet so esoteric that they were impossible to describe to anyone who had not been there with you.

And when he thought of the other things, he could never forget those who had died and those who had suffered more than he had. These were the true moral paragons, whether or not they ever considered it or knew it. Some had taken blasts of shrapnel. Some had been ripped by gut shots from enemy rifles and machine guns. Some had lost limbs. Some had returned with minds pushed so far over the edge by it all that they could not fully come back, even when they were home, and never would. All these years later, he still regarded them as his people, his friends, indeed his lifelong comrades, but it had not really started out that way. The bonds that brought them together and kept them close were powerful and permanent and overwhelming, but they were consequential, not intentional.

He and the others had been thrown together by randomness and fate. They had not chosen the war in which they would fight, or the unit in which they would serve, or the loyalties that would impel their conduct for the remaining decades of their lives. It was not as though they were a band of saints motivated for such sacrifice by a higher calling, or evil warmongers who took delight in battle, but rather that they had been forced to undergo a common travail that caused them to be viewed from the outside in a way that few of them had ever dreamed. They had taken risks that others in their age group had only perceived intellectually, and then had been held up before the country as stark evidence that fighting wars brought moral consequences which only they could bear. Those others who had escaped the risks could secretly be grateful that it was he and his friends who had to live in the world that those consequences had brought upon them. The truth was that they had been forced to trust each other with a completeness that, in many cases, grew into a love as close as family. Life after the war did not diminish that trust.

Like everything else, combat had its upsides and downsides. It was just that the downsides were so low that on any day, they could be fatal, while the upsides—knowing one’s self, and an unbreakable camaraderie—were higher and lasted longer. It had taken a while after the war to understand that no one ever really left the Bush, even if they survived it, that neither the terrors nor the intense bonds would ever disappear, and that all of it would always burn inside him as if it were still the first day or the worst day. So there was no logic in trying to forget it or even to block it out. Every single day and sometimes several times a day, he would think of the vastness of the rice paddies and the sharp, jungle-covered ridgelines and the sounds of artillery crunching into the earth and of sudden rifle fire engulfing him like a horrible loud speaker that had short-circuited and gone out of control and of distant helicopter blades beating into the sky, and he would remember what it was like to smell manioc and rotting thatch and bilious waterbull dung in the sultry evening air as his Marines slipped into the fighting holes they had dug at the edge of this latest village and waited to see if the enemy would come.

And every now and then, he even thought about the killing.

His regiment had become known for moving at night and attacking enemy positions just before dawn. North Vietnamese Army regulars and Main Force Viet Cong soldiers lived in base camps under the jungle canopy in the nearby mountains, just off the Ho Chi Minh Trail where it left the Laotian border. As dusk fell, they would often send patrols down from the mountains, sometimes to attack but also to harass, ambush and interdict the Marines who controlled the valleys. Just before first light they would leave their night positions and move quickly up the wide, mud-packed Speed Trails that lined the valley floor, back into their base camps.

Like yin and yang, the enemy had built their pattern on the way the Marines camped and patrolled, and over time, the better Marine units built new patterns to match the enemy’s.

Walking under the cover of darkness, the Marines would converge on a village or a key hill or a trail intersection that might hold an enemy position. Nearing it, they would silently split in two. Half of the Marines would form a blocking position in the direction the enemy was most likely to retreat if attacked. The other half would form a wide assault line, and just as the sky began to gray, they would rise from behind the paddy dikes and ditches and assault. Thus trapped, the enemy most often would break contact. Knowing they were at a disadvantage if forced to fight in open terrain during daylight, they would flee toward the mountains, which caused them to run directly into the blocking force. Sometimes the target was empty, and the Marines would simply link up and continue their patrol. Sometimes the enemy was prepared, using well-directed fire and contrived terrain features to channel the Marines into close-in ambushes or cleverly concealed booby traps. And sometimes—the best times—the Marines surprised the enemy, cutting their soldiers down like little metal figures in the shooting booths of a small town’s penny arcade when they tried to retreat.

The commanding generals and colonels called this tactic Sweep and Block. The grunts who did the killing called it Flushing the Rabbits. The sweep and block was the most effective tactical maneuver in the open rice paddies and string-like ridgelines of western Quang Nam Province. A rifle platoon of 40 Marines could pull off a sweep and block. So could a rifle company three times that size, or a battalion of four rifle companies, or in some cases, multiple battalions. During one recent sweep and block, three battalions of Marines had trapped a North Vietnamese Army force several times their size, like the proverbial dog that caught the fire truck. Instead of taking up a morning, the two sides had chased and ambushed each other through the villages and ridges, fighting for eight days.

It had taken a while after the war to understand that no one ever really left the Bush, even if they survived it, that neither the terrors nor the intense bonds would ever disappear.

Now they were on the move again. The moon shone above them in the wide and empty sky, reflecting mirror-like in the rain-drenched paddies. They had broken their perimeter at the edge of a village called Phu Phong (4) in the middle of the night, taking down the tent-like poncho hootches, packing up loose tins of C-ration meals and pulling in the trip flares and claymore mines they had placed in front of their fighting holes, counting the grenades and popups that had lain in the parapets, all of this to make sure nothing was left behind for the enemy. Now, hours later, they glided single-file, Indian style, along a packed, mud-slick paddy dike, 10 meters between each man even in the darkness, the column of a hundred heavily laden Marines stretching back for a mile inside the tree line from whence they had just emerged.

They crossed a wide rice paddy, as empty and silent as the moon itself. If this were a movie, they would have filled the screen with an unspoken majesty, their silhouettes cast against the faintly glowing sky. But on the paddy dike, they struggled and cursed and moaned, anonymous and forgotten, fighting a nervous exhaustion. Close-up they seemed more camel-like than kingly. Each Marine’s frame was shrouded in a 12-pound flak jacket and hump-backed from a much heavier pack. Each head was similarly rounded by a steel helmet. Their boots squished in the mud. Sawgrass scratched their legs. Shoulder-fired rockets, claymore mines and bandoliers of ammunition clonked against them, matching the loose rhythm of their footsteps. They carried their M-16 rifles with a familiar ease. Their cartridge belts and flak jacket pockets were heavy with canteens of water, pop-up flares and hand grenades.

They were heading east, toward the coming dawn. Soon they would be flushing rabbits from the village of Phu Binh (3).

The rice paddy ended at the outer edge of the village. A raised dirt trail made a perimeter around the hamlet. Just inside the trail, moat-like, was a deep ditch that channeled a murky stream. An old concrete well built by the French many years before marked the intersection with another trail. They turned onto the other trail, crossing a footbridge over the ditch, and then stepped just inside the village.

At the edge of the village the rice fields smelled of ash from a charred streak left by a recent napalm strike. New odors surrounded them as they entered Phu Binh (3). Following the village’s outer rim they were embraced by a fetid musk wafting up from a nearby pond, and then the perfume of a hundred lotus blossoms. The musk and flowers gave way to wet ash from doused cook fires, powdery manioc fields, and the stench of waterbull pens. A rooster crowed. Dogs yapped at them from nearby thatch porches. A waterbull strained against its nose-hooked leash inside its pen, having been trained by the Viet Cong from birth to shriek and stir at the odor of the gun oil used on American rifles.

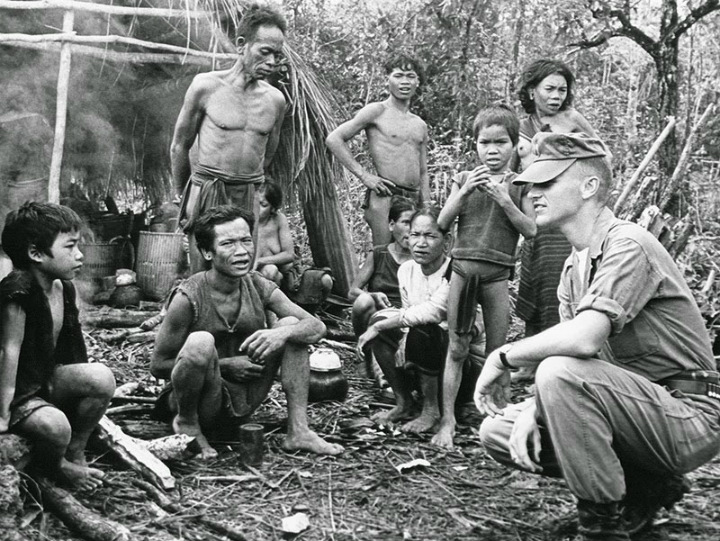

Leaves hung heavy on the trails, lightly touching their necks and faces. Off to their right the village was pitch-black, its inhabitants huddled inside the earthen family bunkers where they spent each night in order to avoid the war. During daylight patrols frail women who had grown old too early would squat on the mud porches, staring quietly as they passed, their faces frozen and unmoving but their eyes electric, missing nothing. They would roll red crumbles of betel nut inside their mouths like a cow’s cud, squirting the juice in front of them, their teeth permanently stained by it and their minds numbed from it, blocking out the daily crisis of a war that was being fought on top of them. Little kids would hold onto the squatting women’s shoulders and necks as if they were lamp posts, their heads shaved except for small tufts in the very front, many of them naked from the waist down, the Bush equivalent of diaper training. The young men were gone, either dead or hiding or camped with the enemy in the mountains.

And in the darkness there was nothing except the roosters crowing and the dogs yapping and the waterbulls, shrieking and stirring.

It happened quickly. The lead platoon silently broke away from their column and set up behind a rise in the earth on the eastern side of the village. The other two platoons crossed a small stream and moved into place behind a high paddy dike on the village’s western edge. Just before dawn, a firefight erupted a thousand meters to their north. They immediately knew that a sister rifle company had trapped an enemy unit in the hamlet of Phu Binh (1). Their faces grew taut. They checked and rechecked their weapons. They crouched behind the high paddy dike as the firefight to their north ebbed and flowed. Rifle and machine-gun fire snapped and crackled through the quiet air, red and green tracers careening and intersecting above them in the bluing sky.

Dawn was breaking. Inside Phu Binh (3) more dogs barked and the roosters crowed. The surprised enemy soldiers began to crawl from the bunkers and move toward the speed trails. In moments they poured out of the village in groups of four and five, dozens of them running westward, heading for the mountains but instead moving directly toward the blocking force. On the right flank at the southern edge of the blocking formation, the Marine machine guns opened up, their tracers forming red curtains of steel in front of the fleeing soldiers. The assault force rose from behind the distant knoll, firing their M-16 rifles from the hip and steadily moving toward them.

The fleeing enemy soldiers were trapped. Some took cover in the mud behind low paddy dikes, setting up a base of fire to protect their comrades. Small groups were shifting directions, probing the blocking position, trying to find an escape route as the gunfire from the Marines grew more intense and ever closer.

Killing the soldier had been personal. Eating his food became a form of Communion.

The Marines in the blocking positions knelt behind the high paddy dike, looking for shadowed targets in the pre-dawn air. To their north, the battle at Phu Binh (1) became more intense, a spillover of heavy rifle and machine gun fire sweeping their left flank. To the east, their front, the firing from the assault force grew heavier, many of the rounds impacting near the blocking force. Theirs had become an instant world of heavy rifle and machine gun fire now coming in from three different sides, mixed with the random impact of rocket-propelled grenades.

They crouched behind the paddy dike to avoid a swelling, heavy burst of fire. Kneeling again and looking over the top of the dike, he caught a dark swirl of motion off to his left, away from the center of the firefight. Three enemy soldiers were jogging just in front of the blocking force, heading south, having escaped the killing zone of the battle at Phu Binh (1). Bent over as they ran, holding their AK-47 rifles low to the ground, they were running perhaps 50 meters in front of the blocking position, well away from the center of the firefight.

The three enemy soldiers did not see the Marines in the blocking force, most of whom were still huddled behind the high dike to avoid the assault force’s gunfire. They began running right toward him, thinking to disappear behind the high paddy dike and reach the speed trail that would take them to the mountains. They would be on top of him within seconds. He had to move quickly, and he knew that this would have to be a careful shot so that he would not hit any of the assaulting Marines on the other side. He grabbed an M-79 grenade launcher from another Marine and stood, exposed to the gunfire of the assault force and also to the advancing enemy soldiers.

The soldier in the middle saw him. They were 30 meters apart, the distance from home plate to first base in a baseball game. The soldier slowed his jog, raising an AK-47 rifle and pointing it at him. But he had already aimed his M-79. He plunked out the 40 millimeter round. The small grenade exploded in the soldier’s chest. The soldier staggered backward and sideways in a quick death dance, like a chicken whose neck had just been wrung and whose head had popped off, but whose muscular system had not yet picked up the brain’s signal that it was dead. The soldier finally fell, face down into the rice. In the darkness and the confusion, the other two enemy soldiers raced along the edge of the paddy dike, almost near enough for the Marines to reach out and touch them. In the chaos, they disappeared.

Somewhere across the vast Pacific, back in what they all liked to call The World, people his age were protesting the war in which he had been sent to fight. Some of them were conjuring up complicated moral visions of what he and the others were doing or maybe should have done instead of fighting. Some hated him, simply for having done it. Some were empathizing, with pity but rarely with respect. Whatever they felt, precious few were capable of understanding what it meant or what it took to have to pull the trigger, of how empty of intellectual thought that moment could be, and how devoid of larger meaning it actually was. Deep inside, he knew that almost every person who was making these larger judgments would have done the same thing, or at least tried to, and if they had not been capable of doing the same thing, or if their moral compulsions were so strong that they could not bring themselves to do it, then they would have lost. And despite all their high-blown moral pronouncements, they would be dead.

The firefight dwindled and then ended. The assault force met the blocking force. The morning sun cooked up the water from the paddies and the ponds. The roosters crowed and the small dogs yapped. The villagers crawled out of their family bunkers. Odors from the cook fires of the villages wafted over them. Despite the vicious killing, all was oddly calm and even normal in this next new day. They checked dead bodies, collected enemy weapons, and called in the medevac helicopters for a handful of Marines who had been wounded. In the odd and haunting normalcy of killing mixed in with the numbing routine of survival, they ate a quick C-ration breakfast. Then laden with gear, underneath a baking sun, they decamped and moved on to the next stop on their patrol route and to the next village or ridgeline where they would set up a new evening perimeter.

He had searched the body of the man he killed. The dead soldier was carrying a tubular cloth strapped diagonally across his chest, like an old Civil War bedroll. The cloth cylinder was filled with dry rice and cracked corn. Inside the soldier’s pack was a red tin of sardines and a mess kit loaded up with cooked rice. NVA packs were prized among Bush Marines for their lightness and for the simplicity of their tie-down pockets. One of his Marines had quickly claimed the soldier’s pack, tossing his own in with the enemy weapons and gear that would be loaded onto the medevac helicopter.

He had eaten the dead soldier’s ration of rice and cracked corn for several days, boiling portions in his canteen cup, mixing in jalapeño peppers and odd spices they would find as they patrolled through the villes, pouring C-ration tins of spiced beef or boned chicken into the canteen cup to make a special feast. There were only 12 meal options in a case of C-rations. From the beginning, several of the meals were unpalatable. Boredom and repetition quickly made about half of them inedible. When it was 95 degrees and one could not escape the boiling sun, there was little appetite for a tin of greasy spaghetti and meatballs or a heavy combination of beef and potatoes. In his first three months in the Bush, he had lost 20 pounds. Now, after seven months he had become sunbaked and spindly, and when he ate, it came down to spiced beef, Spam-like slices of processed ham, or boned chicken.

The dead soldier’s rice was, if not a blessing, certainly an epicurean diversion. And there was more to it. Killing the soldier had been personal. Eating his food became a form of Communion.

Take. Eat. This would have entered my body…

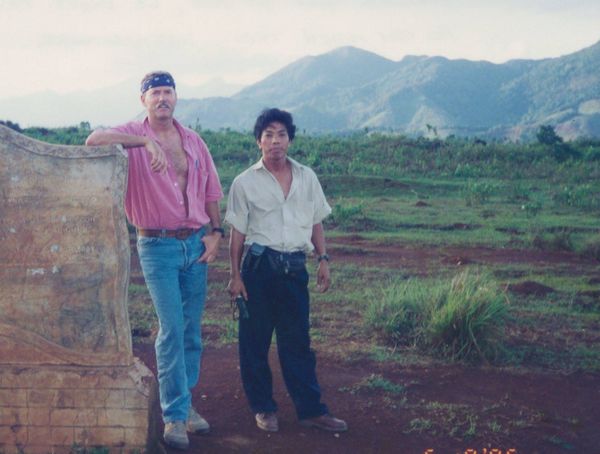

He had also stripped out the dead soldier’s wallet. There were some pictures, including a family photo taken underneath a tall palm tree, everyone smiling and dressed in their best clothes, and a wad of North Vietnamese money, which was useless and whose value he did not understand. In the randomness of combat and the unpredictability of his own survival, he thought that someday he might find the dead NVA soldier’s family. This was not an obsession or even a clear intention. More than anything, it was part of a superstition, a reluctance to destroy the photos and the wallet that had been in the soldier’s pack when he had killed him. So he carried the dead soldier’s wallet and pictures and money in his own pack until he himself was wounded. Then in the confusion of his medevac and the transfer of his gear out of the Bush, everything inside his pack was either lost or stolen. The tangible remains were lost, just as certainly as the soldier’s life itself.

But he was not lying to his grandson, or attempting to soften the young boy’s perceptions, or trying to protect him from some brutal reality that, in their family’s long military tradition, he knew his grandson himself might someday live. The truth was, he rarely did think about killing, at least in a way that haunted his moral underpinnings. Fair was fair. Or, depending on how things went, maybe unfair was unfair. One of them had to lose and one of them had to win, and it had nothing to do with God or law.

There were other times when he had come face to face with this reality, including a final moment when the odds had turned against him and it had all caught up with him, as he had always secretly known it would. In a heavy bamboo thicket at the edge of a musky finger of water he had pointed a pistol into the face of an enemy soldier who had just thrown a grenade at him from a hidden door on top of a concealed, reinforced bunker. He had killed the man, just as he had killed another soldier in a bunker before this one and then another soldier standing in the bunker behind the man he had just shot. Two seconds later, the grenade erupted and blew him off the side of a hill and into the sewer-like, murky stream.

Fair was fair.

The enemy soldier had been smiling. He did not know why. He was not happy about shooting the man but never in all his later years could he conjure up an apology or a regret, other than for the fact that they both had been forced into a violent, inescapable standoff. Of all the long combat he had faced, he remembered this man more than any other, because every morning for the rest of his life as he climbed out of bed he could feel the leavings of that grenade’s explosion and remember the hospitalizations and the surgeries that continued off and on throughout the decades. As those days slipped past him toward the long night that he knew awaited him, he also remembered the things that the explosion had taken away from him, despite his relief over the things that it had not disturbed and the sometimes funny, sometimes irritating things it left behind, like the ringing of the metal detectors when he went through airport security because there was still shrapnel in his body.

And every time he did stop to think about those few seconds that had forever changed his life, he could still see the soldier smiling from inside the trap door of the bunker as the soldier threw the grenade and he shot him in the face. And he wondered why the soldier had seemed to be so happy.

#####

This was published on Politico in June 2015 – here’s the direct link: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/06/jim-webb-fiction-119116

Thank you, Mr. Webb. I’m sure many vets have had to deal with that question from friends, kids, and grandkids. Well said!

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.