Watch Your Six

Watch Your Six

My sumptuous quarters atop the Nhan Vi in Cho Lon were within walking distance of the MACV SOG HQ compound. The sights and smells of that first stroll through those streets were memorable. This suburb of Saigon was known to be full of VC sympathizers; I was therefore mindful of the admonition we received on landing at Tan Son Nhut: Always Watch Your Six. As yet unarmed, I felt particularly vulnerable as I made my way to the SOG compound to check in, to meet the boss, and to draw my weapons (an M-16, a Swedish K submachine gun and a .38 caliber sidearm seemed sufficient to get me through the months ahead).

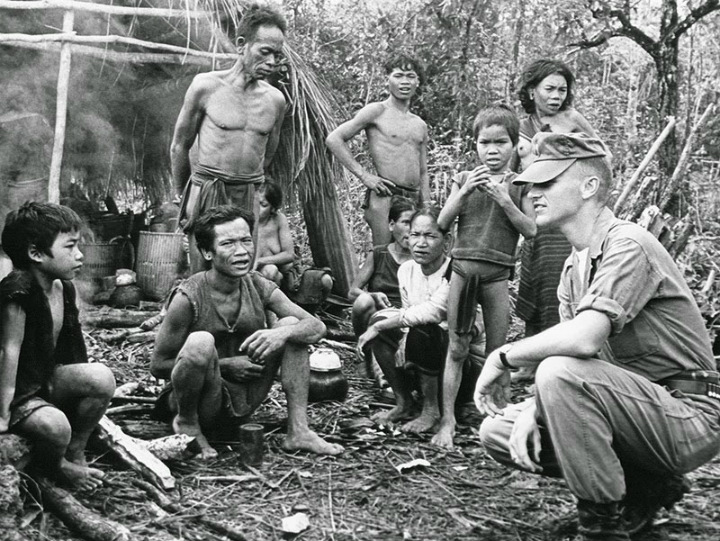

As I approached the compound, I saw a Navy Petty Officer on crutches headed in the same direction. We struck up a conversation which inevitably led to a discussion of his injuries. “M” (Italian surname) was one of SOG’s Navy SEALs, injured on a recent mission to “Study and Observe” a meeting of high level VC in a remote village south of Saigon. “M” impressed me as a guy who would fit right in with Tony Soprano’s crew, including a “Joisey” accent. Tipped off to the high target meeting place, “M” and his team were inserted by helo and made their way to the objective. A rush of the hooch resulted in a successful mission, with only one U.S. casualty–“M” received a punji stick under the right kneecap. Ouch!

With some trepidation, I continued on my way to the third floor office for my “welcome aboard” meeting with the boss. COL John K. Singlaub, crew cut and lean, looked much too young to be a full Colonel.

He was said to be a man who asked direct questions and expected direct answers, who would not tolerate obfuscation and who did not suffer fools lightly. To reinforce this point, I had been told before I arrived in country that a number of his staff officers, some very senior ones included, came to his office once too often unprepared to provide those direct answers and were summarily relieved of their duties and sent back to the U.S. for reassignment. One unfortunate officer was not allowed back in the SOG compound after leaving for lunch. Singlaub would not accept anything short of the best effort from everyone in his organization, in support of the SOG operators whose lives were routinely at risk.

As the Head of the Special Support Group, providing specialized intelligence to his organization, I worked directly with him on a number of highly classified and sensitive operations which required security clearances not held by most of his staff. I was surprised to find how tuned in he was to security considerations and the importance of protecting sensitive intelligence sources. Many field commanders look upon the protection of classified information as an impediment to getting the mission accomplished. I was to find out over the course of that year, and many years later in his autobiography, why COL Singlaub’s appreciation of the need for security was so highly developed.

In 1943, as a young Army Lieutenant, Jack Singlaub volunteered for “hazardous duty behind enemy lines” and was accepted into an organization commanded by General “Wild Bill” Donovan: the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency). After extensive ambush and demolition training, Singlaub was assigned a mission to parachute into France to organize and train French resistance units and conduct sabotage and ambush operations. His case officer was the legendary Bill Casey. As the war wound down in Europe, Singlaub, now a Captain, was transferred to OSS operations in the Pacific.

His first assignment in that theater was, ironically, to equip and train Vietnamese guerillas( Ho Chi Minh’s followers). Their mission was to parachute into an area north of Hanoi and interdict the railroad between Hanoi and Southern China to prevent the movement of Japanese troops and equipment along that strategic route.

While carrying out that mission, word came of the atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese mainland and the imminent surrender of Japan. U.S. concern that the Japanese would kill POWs held in isolated locations led Captain Singlaub to volunteer to lead a mission to rescue Allied POWs from a Japanese prison camp on Hainan Island. At great personal risk, he and his overwhelmingly outnumbered group parachuted into a field next to the POW compound in the middle of the day, and convinced the Japanese military unit to surrender. They successfully liberated hundreds of Australian and Dutch prisoners.

Following the war, Captain Singlaub remained involved in covert operations under the CIA in Manchuria, as that area played a major role in the post-war power struggle between Communism and Capitalism that eventually led to a Communist government on mainland China and, in 1950, the Korean War.

I will only mention the Korean War and Singlaub’s role briefly. He distinguished himself in combat as a battalion commander and was promoted to Major. Eventually, when Singlaub served again in Korea, it would be in 1976 as a General and as the Chief of Staff of the United Nations Command.

A disagreement with President Jimmy Carter over the wisdom of withdrawing all U.S. troops from Korea led to General Singlaub’s reassignment. Had we done what President Carter proposed, most military leaders agree it would have led to another war on the Korean peninsula. Those troops are still there, and peace has prevailed.

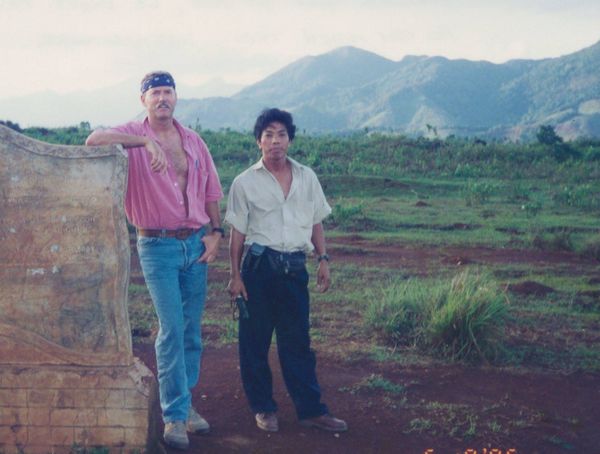

I last saw General Singlaub in 1973, in Spain, when he passed through on an inspection trip. I chatted with him for awhile about old SOG acquaintances, and he told me about his newest challenge — learning to fly helicopters. I understand he is now a qualified helo pilot.

Anyone interested in reading a fascinating account of the life one of America’s real military heroes should get his autobiography: “Hazardous Duty. An American Soldier in the Twentieth Century” by Major General John K. Singlaub, U.S. Army (Ret), with Malcolm McConnell. ISBN 0-671-79229-6.