“My short, crazy Vietnam War.”

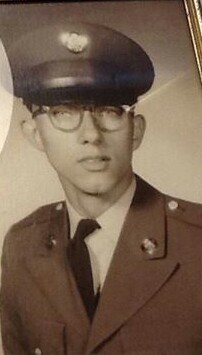

U.S. Army

In the late 1970s, Grady Myers was an artist at the Boise, Idaho Newspaper. I was a young, features editor. We went separately to an office party, where people were supposed to dress as they did in the ’60s. My costume was a giant 45-rpm record. Grady wore fatigues and told entertaining stories about serving in the Vietnam War. I was fascinated. In those days, the military used a lottery system to draft young men. Most guys I grew up with had college deferments or high lottery numbers and managed to avoid Vietnam. If they served, they rarely talked about it. I asked Grady if I could write down his stories. He said yes. I stocked the fridge with Old Milwaukee, bought a cassette recorder, and got him talking. Grady Myers was an M-60 machine gunner with Company C, 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Brigade, and 4th Infantry Division between 1968 and 1969. When I transcribed the tapes, I thought to myself: ‘This is like “M*A*S*H’, only set in Vietnam instead of Korea. Of course, not all of Grady’s stories involved humor or even black humor. People died. People suffered. He suffered. Grady recounted even the saddest parts as if telling an adventure story. His descriptions were those of an artist and a reporter, detailed with sights, sounds, and smells.

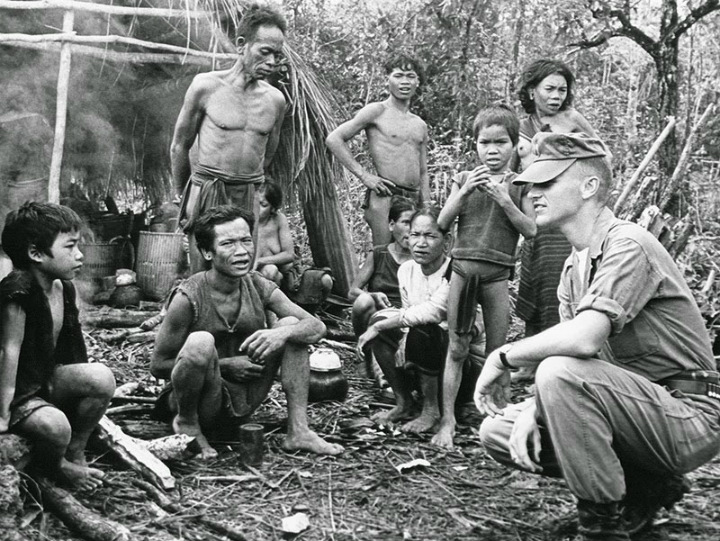

Grady served as an M-60 machine gunner in the U.S. Army’s Company C, 2nd Platoon, 1st Battalion, 8th Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, in late 1968 and early 1969. His Charlie Company comrades knew him as ‘Hoss’. To put my interviews with him in context, I learned about what the Vietnamese called the American War.

Grady had been ‘in-country for a few months at the war’s height when the U.S. had half a million troops in Vietnam. Desperate to keep the troop pipeline filled, the Army was taking people with physical and mental shortcomings who would not have been accepted normally, including Grady, an extremely nearsighted, 19-year-old. Grady and I produced a manuscript that I typed on an electric Smith-Corona and that he illustrated with drawings. We also produced a marriage, our son Jake, a divorce and an enduring friendship. The manuscript stayed in a series of closets and packing boxes. Jake served in the

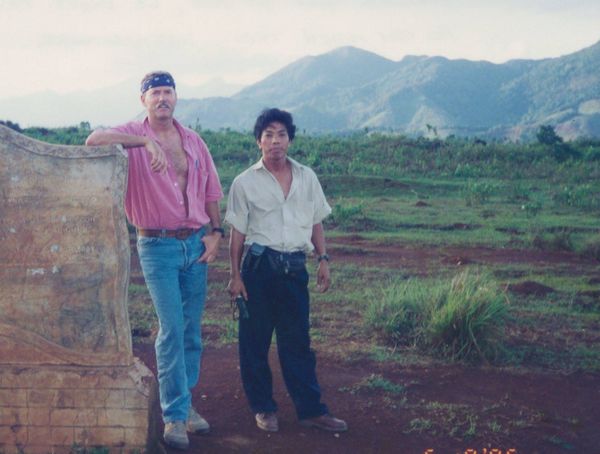

U.S. Air Force like both of his grandfathers did before him. When Grady was in his late 50s, he began thinking about the war a lot. Thanks to information he found on the Internet, he learned things he’d never known, including the fact that he had participated in a military operation dubbed Wayne Grey. After decades of separation from his Army buddies, he discovered that Charlie Company had started to hold reunions. However, he was never able to attend. Health problems had confined Grady to a wheelchair, and, eventually to a nursing home bed. He needed something to occupy his mind. So we dusted off the manuscript.

He propped himself up so he could see his computer and created new artwork. This time there were collages made from Vietnam photos he discovered online. He painstakingly reviewed the manuscript, adding details and more profanity. That’s the way the soldiers talked. When I deleted some cuss words using the argument that they interfered with the narrative flow, his reaction was a begrudging, “OK”, as long as you don’t girl-ify the story

with ‘heck’ and ‘darn’ Grady vividly remembered many experiences in Vietnam. The emotions stuck to his brain like the red tropical dirt stuck to his

body.

He called it a time of ‘intensive’ living. He told his wartime stories, always complete with sound effects. His helicopter imitation was second to none. He did sometimes come down hard on himself. After he reviewed his behavior, described near the end of the book, he e-mailed me to say, “I’m finding I don’t like Spec. Myers very much.” To which I replied, “I liked the young soldier a whole lot. He was so … human.”

Grady was a man of contrasts, with big talent, a small ego, strong language, and a gentle spirit. His tough constitution was legendary, as was his own disregard for his health. A futile war left him in pain, yet he was proud of his military service. He was well acquainted with depression, yet all of his life, he made people laugh. He once looked at a picture of himself in Vietnam, in which his camouflaged helmet accentuated his strong jaw and big eyeglasses. “I was just a kid,” he said. “Hell, we were all just kids.” Now, Grady’s kids have kids. When he died in 2011, at the age of 61 from diabetes and other maladies, I thought it was time to share his stories.

The result is a poignant and sometimes funny memoir, “Boocoo Dinky Dow; My short, crazy Vietnam War.”

~ Julie Titone, Co-author with Grady C. Myers of Boocoo Dinky Dow; My Short, Crazy Vietnam War

–

Grady’s full story appears in the book VietnamandBeyond.com

Veteran stories are interviewed and collected by JennyLasala.com

Phenobarbital speeds the metabolism of many drugs in dogs, including Glucocorticoids Mitotane phenobarbital can lead to higher mitotane dosage requirements in dogs being treated for hyperadrenocorticism Ketoconazole Clomipramine Chloramphenicol conversely, chloramphenicol is a major inhibitor of phenobarbital clearance, and can lead to sedation in dogs on phenobarbital Lidocaine Etodolac Theophylline Digoxin, propranolol, and many others buy cialis online prescription