The Choices We Make

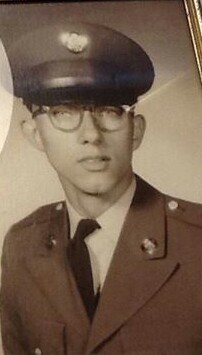

I jumped to the first step and waved a clumsy good bye as the bus driver squished the folding doors between me and my childhood. The bus crested the hill and my Mom, my younger brothers and sisters, and my childhood disappeared below the hazy arch of blacktop. The summer of 1968 had just made the turn toward autumn and I was now a statistic in Uncle Sam’s register.

So begins what would have been my four-year enlistment in the Navy. It was my third choice; a choice I let others make for me. A few months earlier I had made a verbal commitment to join the Marines, and the jungles of Vietnam were waiting. But sometime between the 2-S deferment, the ensuing fist fight with my old man and the love-making with my flower-child girlfriend, I gave up on the Marines and was left with no other choice. It was a choice I would regret for the rest of my life.

Nine months into ny enlistment, my passion for celebrating lead to a drunken collision with a concrete bridge abutment and four days later I regained consciousness in a Navy hospital surrounded by Marines wounded in Vietnam. The guilt planted its roots so deep I vomited from the shame.

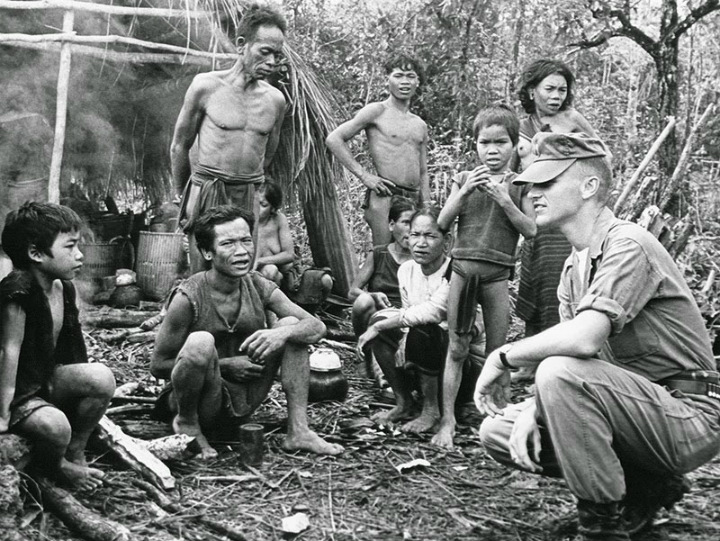

Yeah, me, the Navy party boy, thought I had a lot in common with the wounded Marines who shared the ward; Marines who could have been my comrades in combat. But the only thing I had in common with them was our youth, and that was an illusion. These boys, these men, truly lost their youth sometime after gaining consciousness on their journey from South Vietnam to south Philadelphia.

I lay in the hospital unconscious for three or four days. Once awake, it didn’t take long to know the extent of the damage; left femur broken in three places, skull fracture, brain concussion, both ankles broken, three fractured vertebrae, broken shoulder blade, kidneys bleeding, facial bone fractures and deep cuts and other lacerations that had been “rough stitched”, along with miscellaneous burns and bruises.

I have never forgotten that first moment of consciousness. I craned my neck to look around, trying to understand where I was, what had happened. I gradually took in my surroundings; the rows of beds filled with young boys lying up and down and across from me. I saw kids my own age with raw muscle and bone protruding from where legs and hands and arms used to be, faces lacerated and swollen, bloody eye sockets and bodies burned and charred.

I was confused at first, and then my entire being was hollowed by an urgent and intense fear—a fear that I had died and gone to Hell. The fear was suddenly flushed over by a deep and profound sense of shame and guilt.

These were Marines wounded in Vietnam. No one had to tell me. I knew it in my heart and soul. The irony and the reality lying around me were smothering me, sucking the breath from me, and I felt ashamed. Ashamed for taking an easier way out, ashamed for not being there with them. Ashamed of what these guys, these men, would think of me. Ashamed of the choices I had made.

Someone appeared through the nighttime darkness and stuck a needle in my arm. The soothing warmth of the chemicals washed over me with a temporary relief from the pain, shame and guilt, and I slipped into the darkened no-where land of unconsciousness once again.

Sometime late into the sloth-like sleep, I was awakened by two Navy corpsmen wheeling a new arrival onto the ward. He lay immobile in the hospital bed just to my left. The only thing between us was a small beige cabinet with a black countertop at eye level. The corpsman placed all of the Marine’s belongings, given to him by the Red Cross, in the top drawer; a shaving kit, toothbrush, toothpaste, mouthwash, a black comb, a small transistor radio and a carton of Winston cigarettes.

“Ski, we’ve put your legs back together,” the corpsman quietly assured him. “Dr. Donnolly is the best there is. He’ll be in to see you in the morning. We’ll get you another needle to help you sleep.”

The kid responded with a tight grin and nighttime on Ward 2B fell back into its darkened loneliness and drug-laden calm.

All too often the restless ghosts of war shattered even the deepest morphine-induced silence. The cries of endless nightmares cursed the pitch black air like screams for help from a darkened cave.

Mornings never came soon enough.

(to be continued)

Thank you for sharing this!